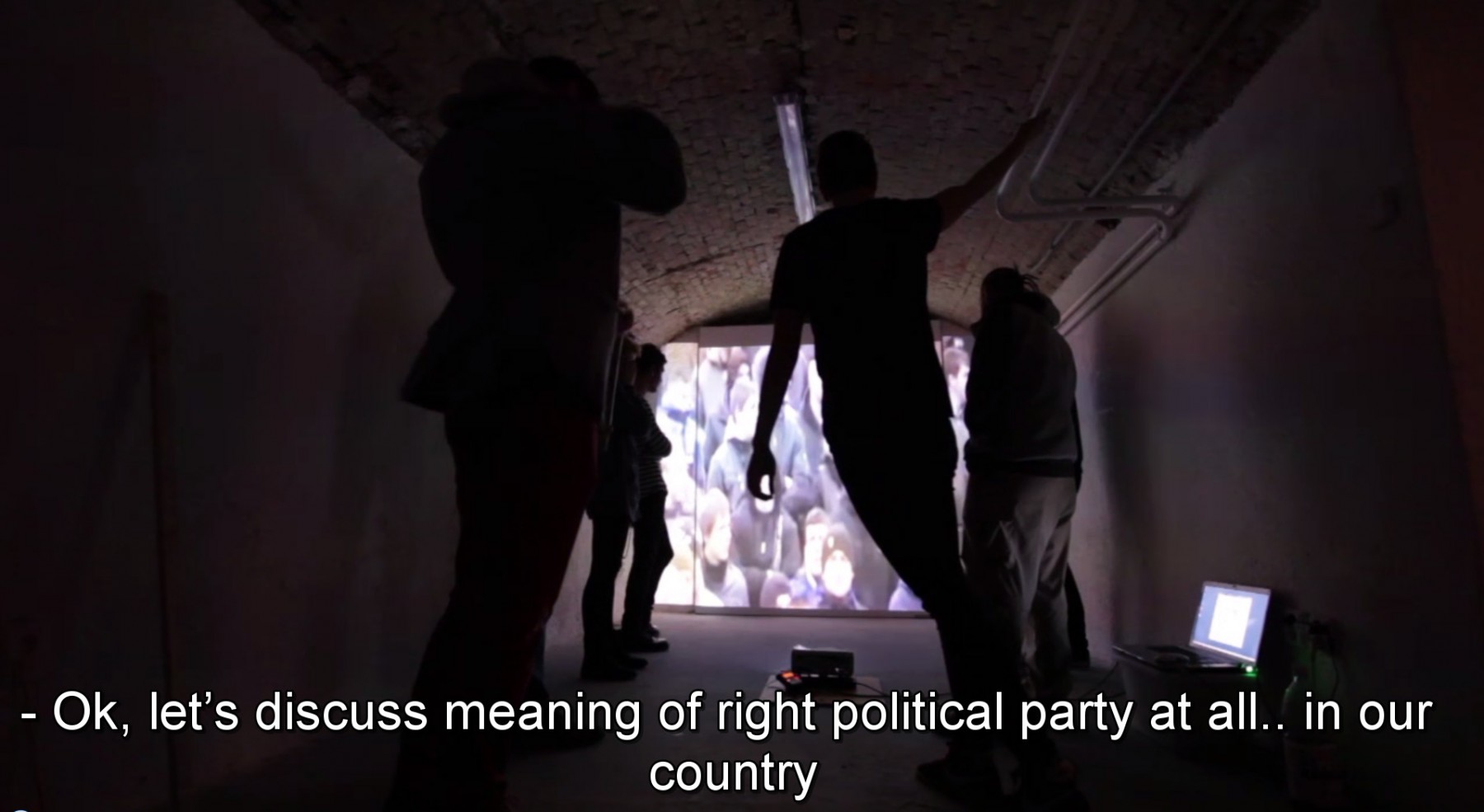

Who Wants to Belong In My Country?

03. 09. – 08. 09. 2016

Article Gallery, Birmingham School of Art, Birmingham

Curated by Karina Cabaniková

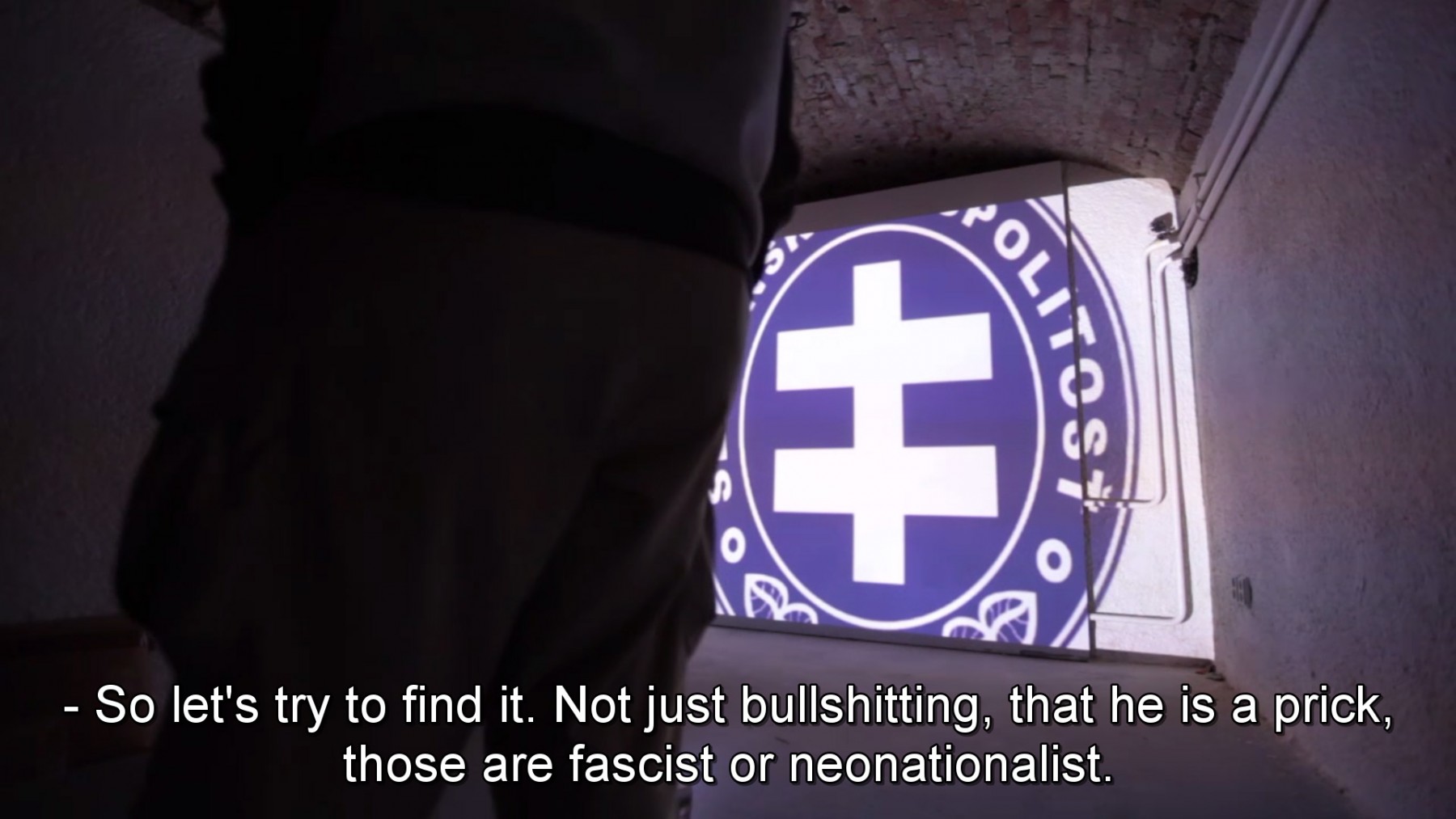

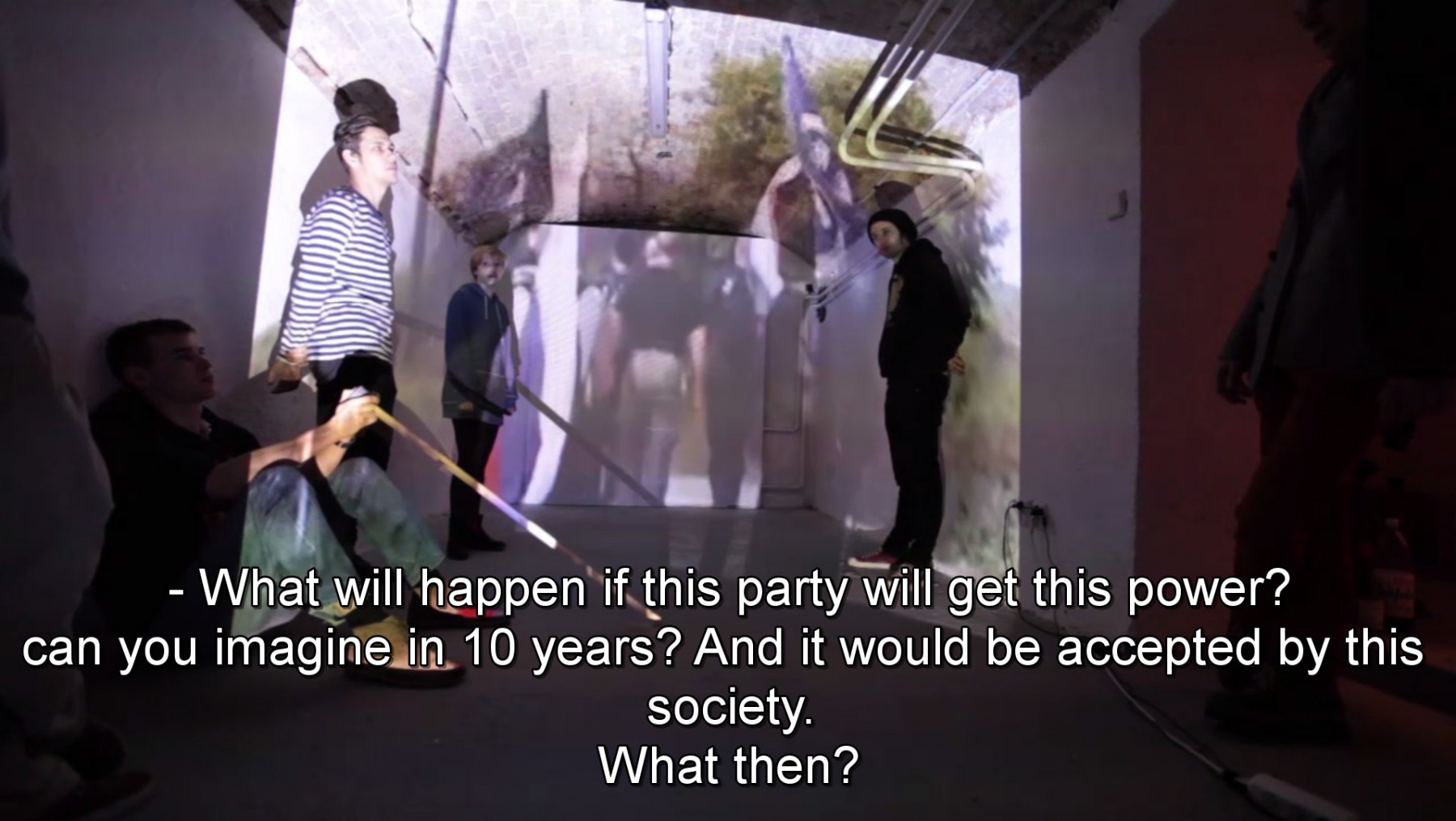

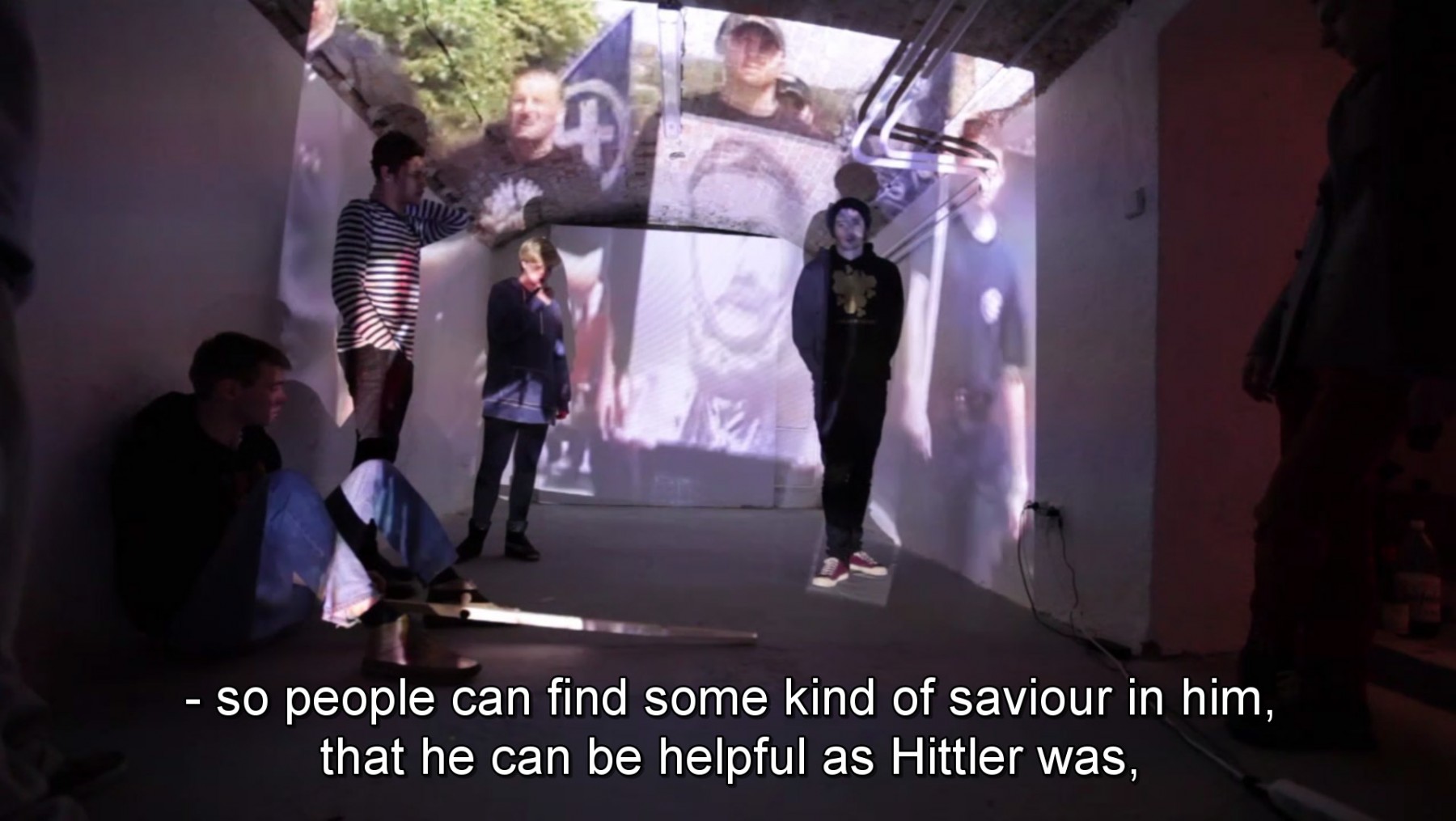

WHO WANTS TO BELONG IN MY COUNTRY?’, a group exhibition of political artwork by Czech and Slovak artists. Titled after a video work by Lenka Kuricová, the exhibition aims to describe the context of the relationship between art and politics, and to highlight the impact of policy actions in visual art in ‘’Czechoslovakian’’ context. Another aim is to create a view of the changing interpretation of ‘’Czechoslovakian’’ political art during postmodernism and its means of expression. Due to the current political situation, the exhibition can be seen with an educative approach. The exhibition features the work of Lenka Garcia Kuricová, Michal Huštaty, Matúš Maťatko, Tomáš Roubal, Zuzana Sabová and Gabriela Zigová.

Establishment of the political art concept is an uncompleted process in the Czech and Slovak art theory scene. Comparing to the Euro-American environment, the situation is additionally complicated by the different position of art in society during the previous regime and takeover period. While in the years 1948 to 1989, the official art in Czechoslovakia had a political role in accordance with state policy and was immediately linked to politics. After 1989 a radical turn takes place towards the declared artistic freedom.

Although the general public often sees the term political art as an art of totalitarian past, this concept did not exist in artistic theory in the Czech Republic and Slovakia previously. In the past to describe the art in accordance with the communist state policy terms like socialist realism and engaged art were used. Whilst Western art of the 20th century shows distinctive lines of freely motivated social criticism, in an environment of real socialism, the oppositional manifestations of art were based on other conditions, and were made in a different context.

Political art (engaged art) is in ‘’Czechoslovakian’’ society met with some resistance due to the influence of the former regime. The resistance is caused by the persistent negative attitude to the politicization of art of the past regime and the suppression of free thought of artists. The symbolic message of artworks sprouts from its openness and its interpretation. On the other hand, political symbolism always leads to a closed interpretation and its restraint to predetermined conventions and rituals. Where art opens new worlds, politics tries to close them up, striving to approve a generally valid and an absolute obligatory meaning. Across of the border political art finds itself in an alternative stream from the outset strongly influenced by the ideas of late surrealism. Gradually moving from a peaceful underground and ends with dissent associated with political persecution. Post-revolutionary demolition of the boundaries of these twobareas is the result of the current state’s ignorant and superficial culture.

The unique approach of the Czechoslovakian nation towards art has always been pretty specific and deviated from world view. This difference in the first postwar period is described in Tomas Pospiszyl’s study Modernistická rozcestí. Pospiszyl demonstrates conflicting opinions and tendencies of global and Czechoslovakian mentality towards the theoreticians from the same period, their original theses are in some respects similar, but after the Second World War, their conclusions differ radically.

Text: Karina Cabaniková